Everyone should write this post once. I submit my entry herewith. I apologize for it being nearly five thousand words. But dumb things often beget dumber things. If that isn’t a proverb, it probably should be.

I should clarify that this probably isn’t the dumbest thing I’ve ever done; it’s the dumbest thing that I’m willing to document. Technically, the dumbest thing I ever did involved a bottle of Bacardi 151 near the corner of Nassau Street and University Place. You don’t want to know. I could chalk that one up to epistemic confusion and/or metaphysical uncertainty, but “hormonal twenty-one year old male” is simpler. Let’s all just agree that Holden Caulfield has already made enough appearances in print. May he rest in peace. The story I choose to tell is far more entertaining, pertaining as it does to real life rather than to an emotional zombie floating aimlessly inside a campus bubble in the early 80’s.

My story begins on May 13, 1985. Ring a bell? No? Well, then you’re probably not from West Philly or its suburbs. That was the day that Wilson Goode, then mayor of Philadelphia, dropped a bomb on a row home to evict its antisocial residents — which he managed to do, except that he also incinerated most of them, along with an entire surrounding neighborhood. Ooops. Interestingly enough, Goode’s given first name is “Woodrow”, his middle name being Wilson. It is difficult to say if that is ironic or fitting, given recent historians’ more accurate formulation of our 28th President, whose transgressions are only now being dragged from under the rug where they had been previously swept for a century …perversely, not far from the corner of Nassau Street and University Place.

Fortunately, my story has nothing to do with that sad affair in 1985, nor are the dumbest things I’ve ever done in the same conversation with dropping a package of C-4 on a densely populated urban neighborhood of row homes. I mention it because the flames leaping from the building on a television screen are my first real memory of where this story begins.

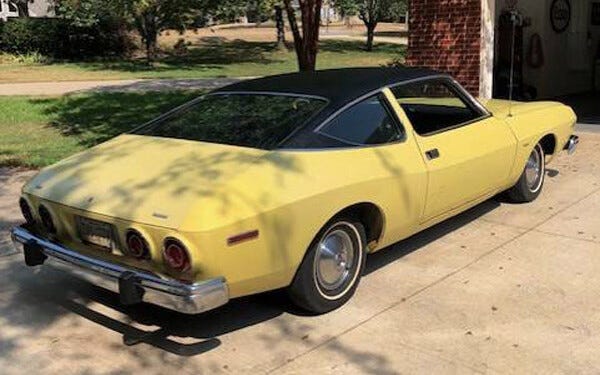

For reasons unknown to me, my father was friendly with the local American Motors dealer. Presumably, this would explain the series of Ramblers that graced our driveway in the 60’s, which led all too naturally to a string of American Motors sedans and coupes through the 1970’s. In fact, I learned how to drive in this sweet ‘74 Matador coupe (well, not this particular one, but one that looked exactly like it — nothing screams “sex” quite like a black vinyl roof on a banana yellow car).

I soon “graduated” to my father’s even sexier ‘75 Matador sedan, pretty much like this:

True fact: One time the battery exploded in this car while I was jump-starting it. That was fun. I somehow evaded blindness and/or permanent facial disfigurement, but the battery acid turned my hoodie sweatshirt into a groovy temporary tie-dye, until the white spots eventually disintegrated, leaving me with a Swiss cheese hoodie. I miss that sweatshirt.

Hmmm. I don’t know. That might count as the second dumbest thing I’ve ever done. However, it is interesting that most of the dumbest things in my past can be connected to American Motors vehicles — my third dumbest thing involved the banana yellow Matador, when I inadvertently enabled yet another Holden Caulfield (rather than impersonated one). It’s good that American Motors went out of business.

Fast forward a few years, I was making a cool $23K/year as an aerospace engineer, feeling full of myself, and I realized it was time to upgrade my ride. My fellow engineers were excited to hear of this (having witnessed the rusty ‘75 Matador) …that is, until I pulled into the parking lot with this sweet, tan 1980 AMC Spirit Kammback (again, not this exact one, but the spittin’ image of it):

My engineering compadres, smitten as they were by the imposing, sensual shapes of F/A-18 and V-22 aircraft, were not amused. No wait, I take that back. They were really amused. As in, “You can’t be serious Tom, it looks like a Gremlin.” But I was. Serious, that is. That car summarized me. It was my automotive doppelganger — looks like a Gremlin but teeming with pathos under the hood.

So let’s get back to May 13, 1985.

That evening I strolled into George T. Fleming & Sons with my father, only to see a few balding sales guys gathered around a tiny television, watching a city block burn to the ground, flinging some now-unrepeatable commentary across the showroom floor. My father exchanged the required pleasantries with the locals, and then we got down to business: I needed a car, and didn’t want to spend toooo much (particularly since I had dumped the first $10,000 I made on multitrack recording equipment — but that’s another story, and partly why this substack has a “Songs” menu).

Old George thought about it briefly, and he realized he had a live one …er, a good fit for a car that nobody wanted. For on his lot was a five year-old tan AMC Spirit with 8,000 miles, previously owned by the prototypical little old lady who used it to go to church. Sure George, sure. Ignoring his friend’s shameless deep dive into the well of groan-inducing car salesman lies, my father took a closer look, eventually rendering judgment: It was up to me but I’d be a fool to pass on it. Who knows, maybe ol’ George was telling the truth? 8,000 miles in five years is what it is.

Setting aside the sales tactics, I looked at my dad and said, “But, but, but… It’s a stick shift! I can’t drive a stick!” You’ll learn, kid. This was as close to a new car as I was getting for $3,000. So I quickly learned to drive a stick, thanks in large part to my older sister’s patient instruction. This sweet ride was mine, and would remain so for six years.

By this time in its proud history, American Motors was operating on fumes. If you ever owned an American Motors vehicle, you will surely agree that these cars were not the auto industry’s finest examples of engineering genius. Everything broke, from transmissions to door handles. AMC engineers often chose from whatever was left after the Big Three manufacturers built their inventory, like birds fighting for crumbs after a party.

But the funny thing is, my little 1980 AMC Spirit turned out to be an exception (“the one that proves the rule”, as my mother would say — no, I don’t understand that expression either). The door and window handles were strangely intact, and remained so. It had no rust. Now, to be fair, this was the most stripped down of stripped down “trim” packages, so there wasn’t much to break — the interior had an AM radio, a cigarette lighter and a glove box. But, darn it, they all worked. The antenna broke at one point, and I replaced it with a comically long one from Radio Shack. But that was about it. This was the little fake Gremlin that could.

Until 1989.

By this time, I had a different job, this one with a Government contractor in Moorestown, New Jersey. Moorestown is an oddly pleasant town, dissonant within its South Jersey milieu, around twenty miles from where I was living at the time. However, the commute involved various two-lane roads dotted with traffic lights, a couple four-lane highways, as well as the infamous Burlington-Bristol bridge — a 1930-vintage, two-lane structure spanning the Delaware River that serviced roughly a hundred times as much daily traffic as it was designed to handle. But the fun really begins when the bridge needs to close in rush hour for passage of large ships. Admittedly, the way it does this is a picture of ancient, brute-force engineering beauty — something the Romans would have appreciated. But tell that to the traffic snaking through Burlington and Bristol.

A Momentous Day

It was a bleak Friday morning when I arrived early at the office, pulled into the lot behind the building and rolled into a space, as I did every morning. But on this particular morning, when I pressed the clutch pedal to complete the process, I felt my foot hit the floor and the sound of grinding gears. “Oh no,” I thought, “my transmission has disintegrated like a space shuttle on a cold January morning!” As I turned off the engine and looked down at my feet, I realized that the news wasn’t nearly that complicated. The transmission had not self-destructed at all; instead, the clutch pedal had broken in half. I don’t mean the clutch inside the engine compartment. I mean the actual pedal near my feet. The assembly had literally broken in half, fractured iron shards on either end, the pedal section now separated from the shaft below, lying lifelessly on the well-worn floor.

Only on an American Motors vehicle does a clutch pedal simply break in half. I suspect that’s not precisely true — but, again, if you have ever owned an American Motors car, you understand why I would propose such a heuristic. One imagines the purchasing guy at AMC, nine years earlier, who probably looked a lot like John Candy, talking to the clutch pedal factory:

Hey Harry, this is Pete over at AMC in Kenosha. Yah, ah, we’re gonna need fifteen hundred clutch pedals over here soon. Can, ah, ya hook me up? <mumbling on the other end> Ah, ya, I see, ya, well, ya know, we’re probably not too too concerned about that. I mean, so they didn’t pass inspection, so what? I mean, the standards of those inspection guys sometimes, hoo-eee, ya know, maybe a tad, ah, “unrealistic” sometimes maybe? A little rich for our blood, ya know? I think we can work that out <more mumbling on the other end> Oh, right, gotcha, ya, I really do appreciate that. That’s a great price. No, god no, don’t put them in the trash. When can you get ‘em here? <more mumbling> Ah, that’s fabulous Harry, Good deal, And, hey, give Doris a kiss for me. You have a good night now…

It was an unsettled day at work, for obvious reasons. I wasn’t exactly sure what to do, as I would need to get home somehow. Would someone tow my car all the way to Pennsylvania? What would that cost? There was no internet or AI companion to untangle these mysteries. The modern cell phone support network was years away. Heck, these cars didn’t even complain if you failed to fasten your seat belt. It was still the neolithic era. Would I never leave this God-forsaken, one-floor hell-hole of an office on Route 38, my life on permanent detour thanks to an AMC clutch pedal?

Morning gave way to afternoon, and afternoon to late afternoon. With no obviously coherent options percolating through my synapses, my mind began to wander. It’s that time of day when you really need a nap, and you can slip into fleeting daydreams and hallucinations. During one such moment, a muse whispered in my ear: Tom, you know darn well that you don’t really need a clutch to drive — clutches are for sissies.

Like most visitors from the depths of metaphysical darkness, this particular muse was not peddling complete falsehoods, at least not technically — just enough truth to be dangerous. You’re not really gonna die if you eat that apple — well at least not immediately, wink wink, nudge nudge. True enough.

In theory, you really can drive a car with a manual transmission without a clutch. If you can reach a particularly zen state, becoming one with your vehicle’s engine, you can sense when the engine RPMs are between gears, allowing you to shift without engaging the clutch. It’s kind of like that old Star Trek episode where Scotty has to restart the warp engines cold, and the most likely outcome was self-annihilation. But if you’re Scotty and you know those engines like the warm feel of a bottle of Macallan single malt, you can make it happen. You might end up being transported back in time — warp fields will do what they do when stressed — but, hey, you can’t have everything.

Over the course of an hour or so, the seduction morphed into concept, which assumed a shape, then an outline, and, finally, a fully ripe plan: I was gonna drive that puppy home without a clutch pedal.

Assuming you can reach that state of zen with your vehicle, you still have two major problems when driving a clutchless car twenty miles through all sorts of traffic conditions, not to mention over a narrow toll bridge that could very possibly be closed. Those are, in order: (1) starting and (2) stopping. Starting is a problem because there is no zen state available. It is quite the opposite: Your only option is to somehow put the car into neutral if it isn’t there already, start the engine, push the car, hop into the driver seat on the fly, and jam the thing into first gear. And that’s okay, if you have a quiet, empty parking lot, and an empty road to enter at your leisure.

Stopping is a different kind of challenge. Short story: You can’t. If you stop, your only recourse is to redo the start procedure, except on a highway in traffic. Or, god forbid, in the middle of the Burlington-Bristol Bridge in rush hour. It takes a deep and abiding faith to believe that a mere mortal can wind his way through South Jersey and parts of an overpopulated Pennsylvania suburb without stopping. I would list some of the highlight-reel challenges, but they will become obvious soon. This type of faith is akin to believing that a functioning cell will arise by chance from a prebiotic soup. Well, not quite, but it’s well up there in the category of “stuff you don’t want to bet your life on”.

To make things even more interesting, I would need to get this process rolling (literally) on my own. The remaining threads of rational me realized that it would be best to wait until rush hour settled down a little — which meant the office was empty, and I was on my own. And vain me didn’t want to admit to anyone that the clutch pedal in my faux Gremlin sheared in two, and that I was about to drive home without a clutch.

As the appointed time drew near, I gaslit myself like a motivational speaker with such phrases as “It will all work out” and (the ‘80’s equivalent of) “You got this” — expressions that mostly offer permission to the temporarily insane to do genuinely stupid things. That rational voice whispering “just have the car towed locally, and ask a sibling to pick you up.” was lost in the noise of my romantic fantasy. By now I was Burt Reynolds, missing only Sally Field to complete the story.

Evening arrived. It was time.

My Ten-Step Countdown to Ecstasy

Step 1 - Start Me Up. Assuming I could coax the car into first gear (and, yes, you too can be a millionaire and never pay taxes), I would need clear sailing onto a four lane highway. So I had to observe said highway for a bit, gauging the ebb and flow through a traffic light about half a mile upstream. Fortunately, I was fresh out of a grad school lab at the time, my observation skills still sharp. The trick was to have the car ready, and then sprint back to the parking lot at the height of the flow of traffic, hoping to time my exit for the expected ebb. I remember the buck and grind of that magical moment when first gear engaged. I can’t tell you how I did it. But I did.

Step 2 - It’s Now or Never. This is the moment when the Apollo astronauts had to decide whether to abort the mission (and land in an ocean somewhere <fart noise>) — or choose glory and head to the moon. I opted for glory. Choosing glory meant turning onto the highway while searching for that first zen state where I could shift into second gear — a state that, to that point, I had not achieved in my eleven years of driving.

Admittedly, this all seems awfully pedestrian compared to a second-stage Saturn rocket engine with about a million pounds of thrust. But we work with what we have to earn the glory available to us. If my glory would be earned in a faux Gremlin on a congested highway in New Jersey, I accepted that role with dignity and honor. After a few antisocial grinding sounds, I felt that oh so sweet slide of the shifter and the exhilarating acceleration into untethered space …er, I mean Route 38. In second gear.

Step 3 - Never Going Back. There’s no going back at this point. And yet, for this marriage to work longer than Stevie Nicks’, I would need to make it to fourth gear. With the entrance to the interstate a couple miles ahead, I had only a couple minutes to figure this out. The line of cars with blaring horns behind me added some pressure to the whole affair, certainly, but I was locked in, cool as James in a Bond flick. Third and fourth gear proved to be putty in my increasingly competent right hand. Like buttah.

Step 4 - Interstate Love Song. With zen state achieved, my auto doppelganger and I had become one. No modern transhuman interface with a machine could ever match the marriage of my right hand with that stick shift that evening. About half way down the interstate I caught myself thinking “this is too easy”. Oh the hubris of youth!

Step 5. - Questions 67 and 68. Fifteen minutes or so later, it dawned on me that I would soon be in Kansas no more, and would instead be playing Pac-Man in a surreal video game world, trying to avoid being eaten by monsters. As I approached the exit, I was overcome by the sick realization that I would be dumped onto another four lane road, similar to the previous one but with more traffic lights. I better figure out this “downshifting without a clutch” thing pretty quickly. What if I didn’t? So many questions, each lacking an answer until its turn arose. This was beginning to look biblical. Who knew that the previously unknown Book of the Spirit would be about an AMC Spirit cruising through New Jersey without a clutch?

Step 6 - Born To Run (on Rte. 130). The next few miles would be either my Agincourt or my Waterloo. I began to recite the St. Crispin’s Day speech to myself.

But we in it shall be rememberèd—

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne'er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition;

And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accurs'd they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin's day.

Okay, I didn’t really — I mean, for starters, there was no band of brothers to rally around my ridiculous stunt. And I doubt that my real-life brothers now think themselves acurs’d, or hold their manhoods cheap, because they were not there. Still, the drama did run deep by this point, the ingredients for a 20th century Shakespeare tragedy spinning up like a Category 5 hurricane in September.

Route 130 is a classic Jersey highway, documenting sixty miles of commercial and industrial neglect between Camden and New Brunswick, with some occasional pastoral respites. But the Burlington segment isn’t one of those. It actually splits into two separate roads through the town, one northbound the other south, connected ladder-style by cross streets and traffic lights. It defines “congestion”. To get to the bridge, I would need to time a light to cross the northbound lanes and then quickly time a second left arrow to turn onto the southbound side. And then deal with a couple additional traffic lights. Oh joy.

I haven’t the first clue how all that worked, but it did. By that time, I felt reasonably confident about moving up or down a gear as needed. I suppose practice makes perfect. And, heck, I had a solid five or ten minutes of clutchless shifting under my belt — I was practically an expert. And yet, no matter how expert I was, the one thing that I could not do is stop.

Step 7 - My God, What Have I Done? So that “no stopping” thing suddenly hit me like… like… well, a million pounds of thrust from a Saturn rocket. It’s one thing to time some penny ante traffic lights and a couple polite, sparse merges. Child’s play. It’s quite another to time the Burlington-Bristol Bridge, with its mother of all poorly-designed access roads. To paraphrase McCoy when the wisdom started to wear off in the middle of Spock’s brain transplant, “What the hell was I thinking???”

But my choices were to continue driving south to Camden, and probably get mugged and left for dead, or take my chances with the bridge. I chose the latter.

I decided that I would make the right turn toward the bridge and quickly assess the situation. If a bridge opening or any other traffic nightmare seemed in progress, I might have one shot at slipping onto an infamous Jersey circle, heading to Camden and getting mugged. So there’s that. This would require quick assessment and instant cost-benefit analysis — just the kind of thing I am really, really bad at. But, again, it’s that or Camden. So I took a deep breath, turned onto the access road, followed the curvy contours, and saw some traffic. But it seemed to be moving, and that’s all that mattered. I made the executive decision to enter the cattle chute and hope for divine intervention.

I realized very quickly that I needed to move slowly, and pretty much ignore the dozens of other drivers that I would be ticking off. I needed to find a quarter (or maybe it was two quarters by then? — I forget), and I needed to leave as much space between me and the cars ahead of me as possible. Buffer zone, baby, buffer zone... I deftly tossed the quarters into the basket, noted (not without a brief flush of pride) the various middle fingers being flashed at me from cars emerging from other toll booths, and continued my quest to defend my buffer zone.

From here, it was pure prayer. Please just keep moving. Please. I’m begging. Believe me folks, it’s in our mutual best interest if y’all… Just. Keep. Moving.

Step 8 - The Bristol Stomp. Prayers were answered. After crossing the bridge in some sort of elevated, out of body state of consciousness borne of terror, I found myself on the briefly pleasant stretch of road leading into Bristol, PA. I suppose that “pleasant” is an interesting way of putting it, since this particular road bisected a large acrylic production facility, where the air always smelled of… well… melted acrylic pellets. But the smell of melted acrylic on that road was the highlight of my day.

Step 9 - Ain’t No Sunshine. You know that part of an action / thriller movie where they lead you to believe that the hero’s problems are solved, but you look at your preferred digital timepiece and it’s only been 83 minutes, so, clearly, the fat lady hasn’t sung just yet? This is that scene — sudden, dark clouds presaging doom after the happy ending was all but assured.

You see, that stinky but otherwise pleasant boulevard to Bristol soon crashes abruptly into a grungy reality. I will make no attempt to describe the geometry in detail. The pleasantries terminate at a dead end, where most traffic will turn left onto another busy road — which passes under a railroad bridge and leads almost immediately to a large intersection with a major thoroughfare. Both intersections typically involve lengthy traffic lights and much waiting. The area has been a choke point for decades, with lines of cars in all directions the norm rather than the exception. My mission, which I had no choice but to accept, was to pass through the two traffic lights without stopping. And the weight of this was now compressing my brain. This had never been done, had it? This really was mission impossible. Where’s Barney when you need him?

As it turns out, it is impossible, strictly speaking, if you pay any heed to the cars behind you, their horns, and the obscene gestures of the people driving them. But if you can tune all that out, and are willing to gamble that none of those drivers are carrying firearms, it becomes a matter of patience, timing, and playing a game of chicken with the lower limits of first gear. As with the bridge ramp, you need to defend a buffer zone like a mama bear defends her cubs.

It was an excruciating three or four minutes, but I somehow navigated this final minefield, eventually finding myself safely on the other side of that major thoroughfare, with no obvious bullet holes in steel or flesh. The roughly six miles of two lane roads and traffic lights that remained would pose little problem, relative to the prior ten minutes of insanity.

Step 10 - Home At Last. As I turned onto the road that I called home, I realized that I would need to stop, and I probably needed a procedure for that. This seemed ironic, since I had spent the past hour obsessing about how to avoid stopping. I remember thinking the best approach would be to gather enough speed to pull into a spot, try to shift to neutral, and then glide unpowered into the promised land. That way, I could just brake, turn off the engine gently, and set the parking brake. Honestly, I have no idea if that is what I ultimately did, as the shock of such a weight suddenly removed from body and soul precluded forming any long term memories. Whatever I did, it worked. And I lived to tell the story.

I know this super highway

This bright familiar sun

I guess that I'm the lucky one

Who wrote that tired sea song?

Set on this peaceful shore

You think you've heard this one before

Well the danger on the rocks is surely past

Still I remain tied to the mast

Could it be that I have found my home at last?

Home at last

Postscript

If you are going to do something dumb, make it an adventure. This was certainly an adventure. And very, very dumb.

So much of my life is ruled by providence. As it turned out, my brother had recently bought his first welding rig (some people accumulate wedding rings, others welding rigs…). My severed clutch pedal seemed like a ripe mini-project for practice’ sake. I have no idea how he negotiated the cramped space in front of the driver’s seat, and managed to both complete the repair and not incinerate himself. But he fully restored my clutch pedal to its original glory, one or two lumps aside.

Sadly, a year or two later I lost my mind and traded the car for a ‘91 Chevy Cavalier (the one and only new car that I will ever own). Someone local quickly bought it from the dealer. I know this because, for a couple years, I routinely drove past the house of the new owner — I knew it was my car because of the ridiculously long, unmistakable antenna. Every trip down that road was heartbreaking. I wanted to stop and just touch it one more time, but I never did.

Three years after that, the Cavalier became the first in a still-unbroken chain of used Chrysler minivans. Car seats don’t fit very well in Cavalier coupes.

I generally don’t miss cars or view them as friends. I view them mostly as essential money pits, unavoidable entrance fees to the suburban life I grew up in. I don’t know where that Cavalier is, and I don’t care. But I do miss that 1980 AMC Spirit. We experienced a lot together. It was me. I mostly buy used Hondas these days. But none will ever be my doppelganger, which I imagine is now part of a skyscraper somewhere in China.

Thanks for reading.

For more reflections about gardening and the broader life lessons it bestows on us, feel free to check out my online book, Life Lessons of a Backyard Gardener, which I am publishing here, one chapter at a time.