NB: I wrote this today without much editing. Sorry if it’s a little disjointed, but the points are important to me. I didn’t want to let it sit around in my draft folder, awaiting attention that I cannot supply at the moment.

The year was 1971. Or maybe it was 1972? — I can’t remember. It was Christmas season, and I sensed a strange buzz in the house. Being one of two afterthought kids in a brood of seven, I was generally out of the loop on matters of particular import to my five older siblings. But even my raw, untuned, little boy spidey sense could tell that something was up.

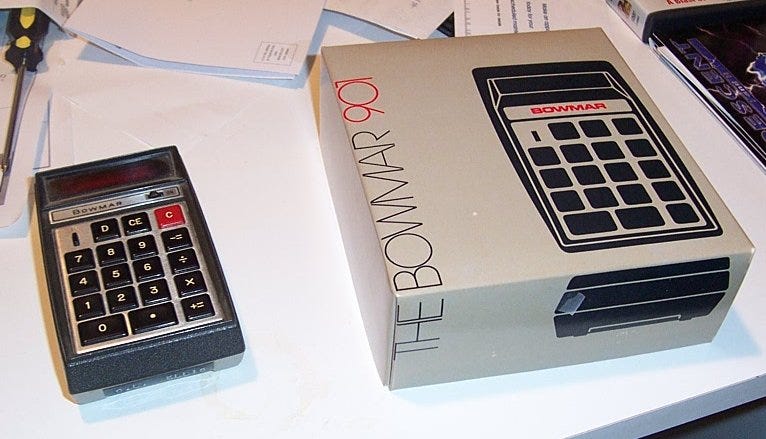

Christmas morning rolled around. My father was a notoriously late riser on Christmas. The customary excruciating delay inched into late morning, as my younger sister and I loitered around the Christmas tree, muttering the 1971 pre-teen equivalent of “WTF???”. When gift time finally arrived, a few of my older brothers giddily handed a present to my father. He opened a box that might as well have belonged to Pandora, for within this compact package was something called a “Bowmar Brain” — one of the first electronic calculators, complete with case, DC adapter and a futuristic-looking red LED display.

The family was awe-struck as we watched this little device multiply 64.0873 by 21.4563, instantly, the confident result glowing almost defiantly in red. I could hear someone say “Check it? Is it right???… Damn…”

My dad was thrilled. To this point, the space age had been deftly translated from afar by ABC’s Jules Bergman on a fuzzy black and white, nineteen-inch television. But now? It had finally made it to suburbia. If there was a definite line between old world and new, ancient and modern, stone age and technocracy, it was neither the industrial revolution nor the nuclear age nor television nor nylon. It was this moment — the day that digital computing entered our everyday lives, in a way that you could touch and feel. At around $100, the price of entry was steep for that time, though we were all about to learn a crushing lesson in economies of scale. At that time, $100 seemed like a small price to pay for instant multiplication and division, screaming in glowy, deific red.

The unstated but clear subtext of that morning of Yuletide enchantment was that nobody knew how the damn thing worked. Such knowledge was reserved for true electronics nerds, most of whom had buzz cuts, lived in Texas and worked for NASA contractors. However, the math that undergirds such deep and profound mysteries would soon filter into school systems — and millions of WWII-era moms would swear at “new math” during homework sessions. But such secrets were not yet public, at least not broadly so. This left the masses in bewilderment at the handheld devices that could now do long division instantly, without pencils, paper or columns of squiggly lines. It was magic.

Things developed quickly from there, as the 1970’s saw the explosion of far more capable and less expensive calculators. Who among us of a certain age doesn’t remember the endless string of “TI-nn” devices in school backpacks? And LED screens sprouting everywhere. Not to mention that unfortunate first wave of personal computers, useful only to tech-savvy college drop-outs dreaming of toppling IBM. Meanwhile, a generation of kids gradually learned about binary math, logic and programming languages. Within a decade or two, the magic had become mundane. There was no ghost in the machine after all. It was all just math operating on silicon chips, hidden beneath a sexy veneer. The nerds had fooled us.

We all witnessed what happened next — personal computers that were something more than door stops, DVDs, the internet, smartphones, broadband, streaming entertainment, the ubiquitous “cloud”, questionable financial instruments, algorithmic money, social networks, an explosion of pornography, and, most recently, idea-laundering machines pretending to be human. These technologies have conspired to change the way we live. Most seemed like magic for a time. Heck, for a while there, everyone thought that Steve Jobs was a genius, and perhaps even a nice guy. Then people discovered what his moody vision did to a generation of young people — a sore subject for another time. The next time some well-funded west coast dude in a black turtleneck tries to change the world…

Oooops. It turns out that we have not learned our lesson about well-funded west coast dudes dressed in iconic, self-actualizing costumes. In fact, we have already entered Round 3 (the social networks can reasonably claim Round 2). And its name is “artificial intelligence”. But friends call it “AI”. AI is a big subject, way too big for one snarky article that I’m trying to keep under 2,000 words. So let’s generalize for brevity. Then I will get to my point. Good? Good.

Most modern AI is based on so-called “neural networks”. For a lot of people, neural networks are the things that make Data from Star Trek TNG tick. They make machines human — because humans are just neural networks made from meat, right? Or so the story goes. It’s all nonsense, of course. A neural network is a mathematical structure that computes things — much like a Bowmar Brain did, just with a lot more calculations. Human brains don’t work like that. The brain is not a computing device. Neural networks emulate human brains in the same way that a pile of dog vomit emulates the Mona Lisa. Modern AI has much more in common with that “primitive” Bowmar Brain than it has with any human. Hold that thought — I will return to it.

I don’t want to get too technical, but there are a couple important things to understand about what a neural network is and is not. A neural network is not a physical thing. It has no neurons; the “neurons” in a neural network are just data structures in computer memory that pass data between each other (if “data structure” sounds intimidating, think “list of numbers arranged in rows and columns”, and you won’t be far off). The network has no essence, no being, no purpose, no “self” outside of the data bits that pass through it.

Computer programs not deemed “AI” have been doing this kind of thing for a very long time. So why is it so special now? A long time ago, data scientists with decent math skills realized that you could stack a lot of these virtual “neurons” in computer memory, and do a ton of calculations that move data between neurons in different combinations. And if you run enough samples through such a thing, you can “tune” it to recognize specific patterns that are useful to recognize — say, a license plate or a fingerprint. Think of it as turning knobs to tune a radio. In other words, if you can characterize something as data (like, say, a photo), and if you have enough samples of that something, then you can “train” a neural network to recognize it in new samples (as an aside, one big problem with neural networks is there is no way of knowing if the network learned about the “something” that you targeted, or if it learned something else — because the network isn’t conscious, and it has no idea of what you are trying to get it to learn).

I cannot stress this enough: This is all that neural networks do. They extract patterns in data. Any claim to the contrary is nonsense, hype or both.

But this is not the end of the argument. Why? Because AI systems — particularly generative systems like ChatGPT — are more than simply neural networks. Such systems contain many computing layers, some of which inject human knowledge and preferences into the system. For example, a pre-processor layer might modifies user-supplied prompts to ensure that certain desirable cultural outcomes are achieved. In other words, they cheat. Similarly, when AI’s “cheat”, or display apparent deception or some other seemingly human trait, that happens only because a human wanted the system to display that characteristic, and was willing to rig the system accordingly. Neural networks cannot do this on their own. When you hear about an AI acting like a human, you can be 100% confident that a human injected the data or rules required to obtain that behavior.

Apple’s own researchers recently concluded that current AI systems have not progressed much beyond pattern-matching, despite all of the injection of biases and corrections by humans. We are nowhere near “Artificial General Intelligence”, or AGI — i.e., a machine that can think. Current AI systems do not “reason”, or learn to reason — they create the illusion of reasoning through advanced pattern-matching. It’s a parlor trick — a super useful parlor trick sometimes, but still a parlor trick.

So what’s my point? Yes, part of my point is that modern AI systems are much closer to my dad’s ‘71 vintage Bowmar Brain calculator than they are to the human brain (except that Bowmar Brains always delivered the right answer). I’m sure that point is obvious by now. But I’m not particularly concerned if people refuse to accept this. One can be delusional on this point without causing harm.

What concerns me is a class of writers, podcasters and intellectuals who are creating a cottage industry of insinuating that AI systems are somehow tapping into a conscious or spiritual realm. People like Rod Dreher are heavily on this train, and it is irresponsible. Rod is a talented writer. While a little too far down the populist/nationalist rabbit hole for my tastes, Rod is a genuinely decent guy who offers perceptive insights on a range of cultural, political and spiritual issues. But he wants to make connections with AI that simply do not exist. He repeatedly suggests that AI systems could be channeling beings from spiritual realms. I have heard other podcasters make similar claims about AI systems having “agency”. These are trained theologians who write for respectable publications, not quacks and demagogues. But all of these claims are simply wrong. Dangerously wrong.

Why “dangerously”? Because they misinform and alarm. Most people don’t know how AI works. That includes the writers and podcasters whom I call out here. All they know is what they hear and read from people who claim to be informed — who in turn are regurgitating the claims and insinuations of others. They want to be alarmed. They want explanations that comport with their worldviews, just as 20th century dispensationalist preachers and writers wanted to attach every major world event to a verse in the Book of Revelation.

None of these people has ever written the code for a neural network from scratch, as I have. If any have, then I can almost guarantee that they have financial interests to defend, and are willing to lie for their cause. Because anyone who knows how neural networks work knows that they are simply number-crunching machines that dutifully perform well-established vector math on mountains of data. Can that be useful? Damn straight it can — these are incredibly powerful tools. The age of conversing with your computer a la Captain Kirk is here. It is real, and it is spectacular.

I am not here to bury AI. But I am here to figuratively bury people who are spreading lies about it, and scaring the daylights out of spiritually-inclined people. These folks need to get educated, and they need to stop doing this. The fact that some smart, articulate opinion leader with a Ph.D. in Medieval Cultural Studies is on board with ghosts in machines does not make them real. Well, the ghosts might be real, who knows — that’s a separate subject. But the machines are 100% ghost-free.

We are back to the age of the Bowmar Brain: Nobody knows how the damn thing works. Except, as was the case in 1971, somebody actually does. Many of those who don’t know how they work assume it is magic rather than math, a conspiracy rather than a parlor trick. But it isn’t magic. Or a conspiracy. It is math. And, to some extent, a parlor trick.

Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me. I won’t be fooled again. And you shouldn’t either. AI poses many dangers to humanity, as its many benefits also unfold. But we won’t be needing Dan Aykroyd donning a backpack to cure any of them.