NOTE: This is Chapter 11 of my online book, which is a work in progress. Enjoy.

It is a particularly nice day in March. The last bits of snow have succumbed to the burgeoning spring sun. Scattered rosettes of green grass presage the annual tune-up of the mower. Newly defrosted garden beds beckon for their early-season sprucing. And so I head back to the composting area — still wet and muddy back there, but it feels good to be immersed in warmish, moist air after an endless winter. And I fill a wheel barrow with black gold. Rolling it back to the beds awakens my soul, pouring renewing moisture on a spirit desiccated by months of dry, indoor air and dark, sedentary evenings.

As I distribute my primo soil booster around the beds, I stumble on some discordant artifacts, almost like finding cell phones scattered in Jurassic rock. It turns out that my compost fossils are also communication devices of a sort, but they were built to convey only one message: e.g., “I’m a banana”. I am, of course, referring to PLU stickers from the supermarket produce aisle. Like annoying ear worms, they just won’t go away. Who among us cannot identify #4011? Or #4046? It matters not; they are all indestructible, cycling through your garden for years after sleuthily slipping into the composting system. Bacteria and creepy crawlies cannot touch them. The wiser me has learned to strip all bananas and avocados ASAP, before the kids get their hands on them and ignore proper composting etiquette. But that epiphany appeared later in life. And so my garden will forever harbor remnants of these ancient and eternal friends, resurfacing annually as memorials to silky smoothies and epic bowls of guacamole from days past.

Other curiosities emerge from a sojourn through the soil, although curiosity can be in the eye of the beholder. For me, one of those is old egg shells. My family consumes a lot of eggs. Eggs are good. Eggs are versatile. Eggs are amazing feats of bioengineering. And the shell of almost every egg that my family consumes finds its way to the compost pile. Given the thousand or so eggs that we use in a year, and given the sturdiness of an average egg shell, I often wonder why I see so few of them in the compost after merely six months of spirited decomposition. An eggshell is no PLU sticker, but it ain’t no banana peel either. But most disintegrate and disappear, releasing their calcium and other valuable nutrients into the compost medium — nature can be ruthlessly efficient with its own. Still, a few hardy pilgrims always manage to survive. And those intrepid survivors pique my imagination.

The PLU stickers mostly generate perfunctory sighs of acceptance, but the egg shells inspire deeper, richer thoughts. It occurs to me that each little shard of shell has a history, a story to tell. What omelet or loaf of zucchini bread did that egg help to create? How did the carton get to the supermarket? When exactly did the chicken lay the egg? How old was the chicken? Did it ever cross the road? Where was it born? Is it still laying eggs somewhere? How did it get to the egg farm, if it wasn’t born there? Who owned the truck that drove the chicklets? How long has that guy or gal been driving chickens around the countryside? Does he or she do much social networking? Who made the truck? Who started the company that hatches the chickens? Who designed the hatcheries? When was the last time that hatchery technology experienced a disruptive change that rocked the world of chicken folk? How long have people been raising chickens anyway? Did William the Conqueror have chickens? Aristotle? Sargon? Is there an Indo-European word for chicken?

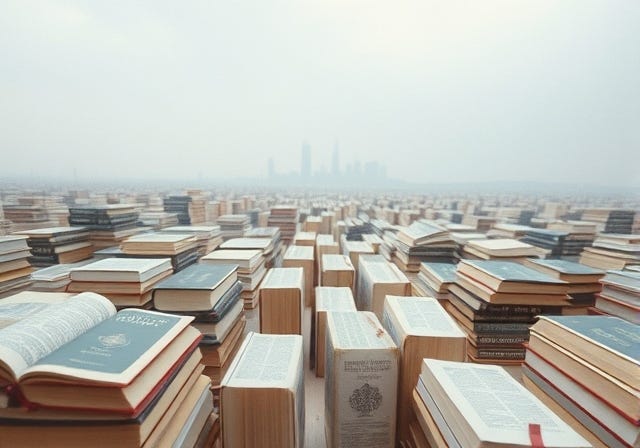

These sound like silly, inane questions. And they are, at least at face value. But they have answers. Many answers might be unavailable to us, but all exist -- thousands of answers to thousands of unasked questions, thousands of metaphorical pixels behind a mammoth metaphorical picture. The more pixels, the sharper the image. Documentation. Real history. Yet mostly unobtainable. The crude, highly pixelated histories can mislead, as our minds fabricate the missing information, bending and twisting real data to fit our preferred aesthetic. We often do this with family lore, which frequently disintegrates at the brick wall of ancestry records. Sometimes we substitute the cultural norms of today, which are often foreign to the world of yesterday. But if we ask enough questions, and demand enough answers, the tidal wave of truth ultimately overwhelms. And we learn. The good back stories matter.

Granted, the history behind an egg shell in my compost seems a little silly in the context of, say, Chinese dynastic succession, or the Reformation, or the Enlightenment, or early human migration into the Americas. But that is our human instinct to prioritize within a hopelessly complex universe. If you widen your perspective sufficiently, all histories intersect in interesting and sometimes profound ways. As Charlie Brown once said of Pig-Pen, “Don't think of it as dust… he may be carrying the soil that was trod upon by Solomon. Or Nebuchadnezzar. Or Genghis Khan!” And I conclude that even dust has a back story!

An “integral” is a mathematical technique that scientists use to calculate important values. Don’t cringe; here is a simple illustration: Let’s say you need to know the area of a rectangle, but you don’t know how long or how high it is (so multiplying base times height is out of the question). Conveniently, someone gives you a narrow slip of paper that exactly matches the height of your rectangle. And, coincidentally, you know the area of the slip of paper. All you need to do is count the number of slips of paper that fit inside your rectangle, multiply, and that will tell you the area. Congratulations! -- you just did an integral. Sure, this example is tediously simple; in real-world calculations with strange shapes, you have lots of imaginary slips of paper of different height, each infinitely narrow – welcome to the mind-bending world of calculus. But rockets would never go to the moon or Mars or Pluto, your cell phone would not exist, and most of the technology that you use every day would cease to be without this seemingly pointless technique.

Our perception of time is much like those narrow slips of paper. When spliced together over the years, the slices of time build the shape of who we are, the breadth and substance of our lives. Of course, human lives are far more complex than cell phones and trips to the moon. There are no fancy equations that can be “integrated” to summarize and quantify the human sojourn, no predictable orbits or trajectories, no calculable quantities, no computer simulations to approximate it. We can only observe it, not calculate it.

For thirty years or so, I have so observed, capturing my own set of time slices in a personal log, recording more or less what I have done with every hour of every day of my adult life. Combined with other sources, it lets me do very rough “integrals” for different periods of my life, reconstructing small parts of my own back story through different periods of life’s journey. I find this helpful, if hopelessly crude and imprecise. When performing such exercises, we inevitably discover that our individual life trajectories intersect thousands of others. It is impossible to construct any truly accurate back story in a vacuum. History is an intractable tangle of interactions -- mostly unseen, undocumented and forgotten, like the eggshells and banana peels in a compost pile. This almost infinite hidden depth within all of our back stories is priceless information, like the calcium in the egg shells and the potassium in the bananas. If we could read and know the true back stories of everyone we know, our understanding of the world would change, our motivations would shift, our internal compassion and empathy meters would spike, and our outlooks would likely be radically different. The calculus of life is fantastically complicated when we consider our place within an infinite set of intersecting, interacting histories. Your past affects other people; their pasts affect you.

The egg shells in my compost? They help keep the ends of my tomatoes from rotting (yes, that’s a thing), but who knows what else they are doing? So God bless the chickens that laid those eggs. God bless the person who drove the hatchlings. God bless the person who secured the wheel hubs to that person’s truck. Like most of us, they probably have no real appreciation of the impact they have on the world. We can never truly know. But once in a while we need to step back, stick our hand in the soil, and pluck out another scene from a back story where we’ve been playwright, actor and audience. Though most of those scenes are lost to history, the ones that remain pluckable can explain a lot. And sometimes help to build a better future.

We are the integral of what we were. Do the calculations.