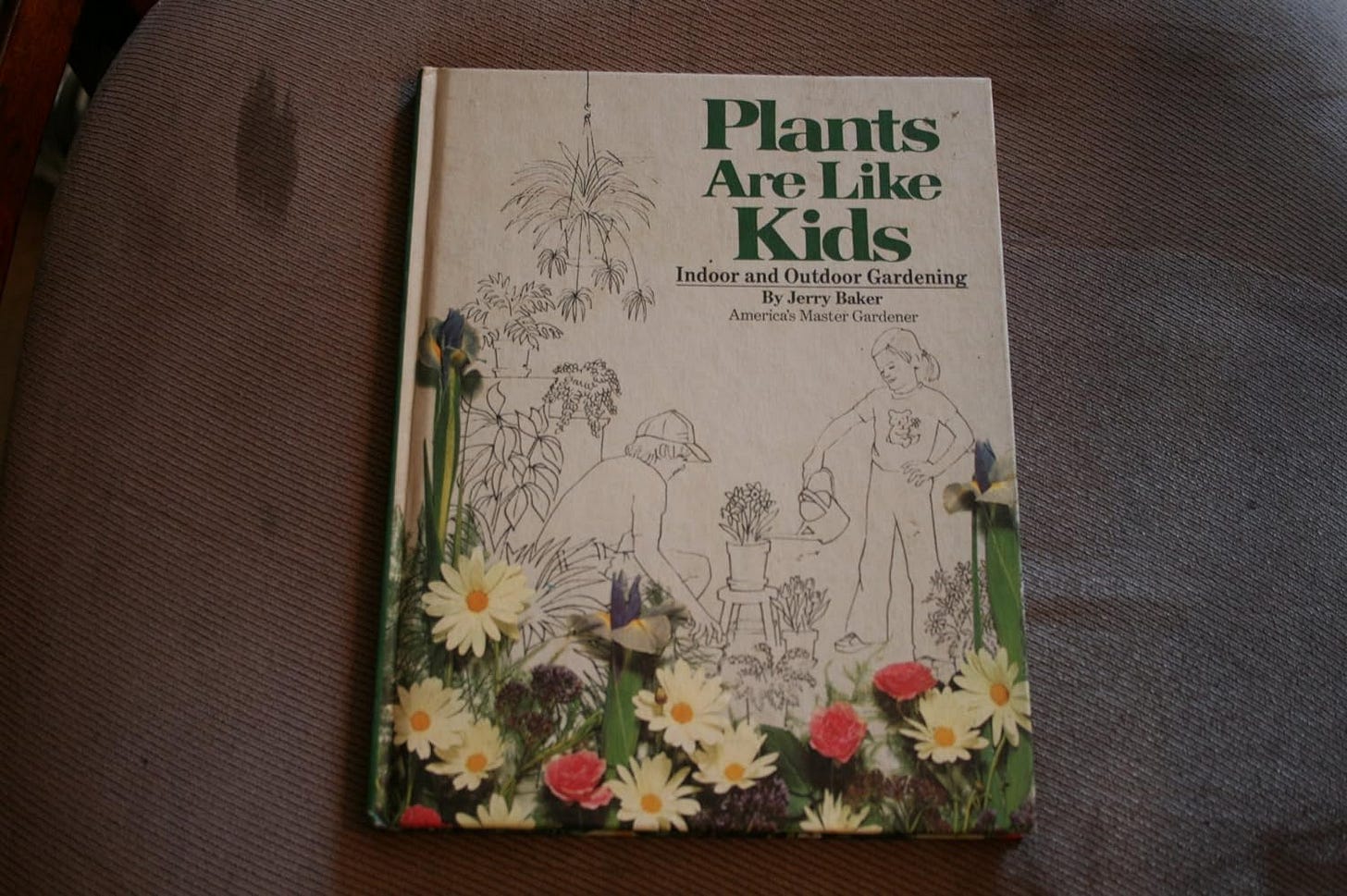

The first book about gardening that I ever owned was Jerry Baker’s Plants Are Like Kids. My brother gave it to me for Christmas, which was more than a little unexpected. He is eleven years older than I am, and so at the time he was living in a different universe than thirteen year-old me. As a kid on the tail end of a large family, you mostly experience alternating wrath and disinterest, so a Christmas present – a very thoughtful and cool present – seemed a distant possibility. But there it was.

I mention this for two reasons.

First, I would argue that people are like plants, perhaps more in keeping with Baker’s earlier title Plants Are Like People – which I never read, but I will cheerfully seize the title for my own purposes. Plants have good days and bad days. They get fungus. They get needy. They get bugs. And then one day they turn around and give you a flower or a tomato. And second, because of that, we need to accept the bad with the good …with plants and with people. You don’t know what vine borer is lurking at the base of your squash plant, ready to ruin its day. And you don’t know what lousy thing happened to a person today that rendered some anticipated polite gesture impossible to execute, or even think about. Life is challenging and complex, whether you have a nervous system or you photosynthesize for a living. Stuff happens. With everyone. You don’t unload on your tomato plant just because a couple leaves turned yellow. And there’s no reason to toss humans under buses either. Be kind. Assume the best. And you’ll see lots of flowers, I promise.

Kids are people too, or at least that’s what I’ve read in books. As a parent, I wonder sometimes. Either way, Jerry Baker was right; plants and kids do have a lot in common. And his book – the one I actually read -- was tuned to kids’ self-awareness. As a kid, I ate up chapters like “Don’t Shiver Their Timbers”, which related watering your garden at night to sleeping with cold feet, or something along those lines (it was forty five years ago, and my copy of the book is long gone, presumably discarded by that clutter-reducing machine known as mom). Baker was notorious for using weird household concoctions in the garden, like mixing a can of coke and some ammonia in a sprayer, because, you know, sugar and nitrogen are good for the soil. Don’t quote me on that. The details do not matter. But they did matter to a thirteen year old boy, for whom all of that crazy household cleaner stuff was gold. “Mom, can I buy a sprayer and a bottle of coke?” Sigh.

I am well on the other side of parenthood now. From this vantage, I recognize that Baker’s cutesy correlations and concoctions were fun, but they obscured deeper lessons, buried well below the surface of the questionable gardening advice. Yes, plants are like kids. And, in some ways, raising plants is a lot like raising kids. So, in that spirit, allow me to opine about one of my favorite, later-in-life garden discoveries… butternut squash. Oh, sure, we could just as well discuss acorn squash. Or pumpkins. Or even tomatoes. Our lesson would be the same. But I like to grow butternut squash. It is one of the staplest of staple plants that you can grow at home. Give it some love and ample space to wander, and a single vine will supply enough silky goodness to keep you straight through winter.

In principle, growing garden plants from seeds is simple. You beg, borrow or steal (or maybe – horrors -- buy) some seeds and some soil, bury the seeds in the soil, add some water, and wait. Easy as pie, right? Actually, oft times yes, particularly with certain larger seeds like green beans, cucumbers, and squash. Plenty of things can go wrong, of course, but I will leave most of those situations and painfully stretched metaphors to other lessons. For now, I will focus on two issues that are easy to overlook if you have never turned a tiny seed into forty pounds of tomatoes.

I will assume your babies have germinated, and, like new parents home from the hospital, you are saying “Uh, what’s next?” Well, you want your babies to grow up to be productive and happy, that’s what. Just like your kids. And the way you do that with seedlings is to foster something that I call “seedling momentum”. Seedling momentum is a slick slogan for “if you ain’t growin’ you’re dyin’ ”. This is one of those really important ideas that flies against the intuition of new gardeners, who thus routinely ignore it, and who then routinely make one of the biggest mistakes that gardeners make -- that is, starting seeds indoors too early. So, what’s so bad about starting early? Well, nothing, if you have a greenhouse where seedlings can flourish after they reach a certain size. For the rest of us in northern climes, if you start your prized heirloom tomatoes in January, then March and April are going to be long, tortuous months indeed, as you pace the floors wondering how to keep two foot tomato plants thriving with limited light. Without professional grade facilities, the plants will lose their momentum, becoming rootbound, spindly and weak. When you finally do bring such plants outside, they are unable to face the world. At best they must bide time as they attempt to build strength; at worst they wither and die in the face of real wind and sun. On the other hand, if you wait until mid March -- or even early April -- to sow the seeds, you will have strong, healthy plants by mid May, full of momentum, ready to face the world. Patience, grasshopper -- waiting is better.

But even the most momentous seedlings require an additional step. Gardeners call it the “hardening off” period. Hardening off is the process of transitioning your delicate babies to the challenges of the outdoors. Let’s clarify something: The sun is a star. A freakin’ star. Yes, it is ninety million miles away -- that ain’t much for a star. Moving a plant from a puny plant light and placid, indoor air to full sun and wind is a big deal. It’s like dropping your toddler off at Penn Station in New York and expecting her to find a job and survive. There are required interim steps.

What does all of this have to do with butternut squash? Do an experiment. Grow two butternut squash plants. Give them momentum indoors, then put them in slightly larger pots as you begin to harden them off on your patio, first for a couple hours, then all day but bringing them in at night, and then all day under the star… er… sun. Soon it will be time to transplant them to the garden – to drop them off at Penn Station to make a living. Go ahead and do this for one of the plants, but leave the other in the pot on the patio. Then observe as a few days dissolve into a few weeks, and then months. After a couple months, the plant you released to the garden will be ten to fifteen feet long, with half a dozen cute little butternut squashes dangling from its various stems. The one you left in the pot …not so much. It will likely have one stem, maybe two to three feet long, with maybe a couple flowers. And maybe a single tiny squash. It lost its momentum weeks ago. Even if you put this plant in the ground now, it will never attain the glory of its twin. Such is the importance of seedling momentum.

Seedlings need momentum, and so do people – kids in particular. They thrive on new challenges, new experiences, new words, new friends, new …everything. They need to grow. If you put them in boxes with boundaries, you get the two foot squash plant with a couple flowers. If you put them out in the garden, they grow squash. You can decide what’s best.

Assume the best and give kids room to grow.